You worked with your team to identify the tasks, carefully worked through dependencies, got thoughtful estimates from your most experienced people, built a well-formed schedule, and confidently presented the results to the executives. They don’t ask about your process, they don’t question your assumptions, they don’t ask what they can do to trim scope or adjust resources… they just hate the answer. Sound familiar? What next?

Schedule optimization is a dark art – performed by a cabal of shadowy ninja project managers in the dead of night behind closed. The first rule of Optimization Club: Don’t discuss Optimization Club. That’s the myth. Let’s shatter it by sharing some general schedule improvement tips.

Before we start, two disclaimers:

Disclaimers behind us, let’s look at ten approaches to credibly compress a schedule. These tips might apply to any task, but focus your attention on the critical path where it matters most:

Zero) Can “deadlines” be negotiated? I know, I said nine strategies. Step zero is a meta strategy and doesn’t count toward the total. Before engaging in potentially costly and risky schedule compression, review the rationale for the schedule target. What is the business impact of missing the target date? If missing the date by a week will incur a $1000 penalty, don’t rush to spend $5000 to make the date before considering alternatives. I don’t use the word “deadline” in polite company. The word comes from the American prison system in the 19th century. It was a line drawn near the wall. Crossing the line gave guards permission to shoot to kill.

How many of your projects really have deadlines? How often does a Hearse carry away teams who miss a schedule target? Used poorly, these strategies won’t help much, but they can hurt a lot. Use them wisely.

One) Where would adding people meaningfully speed up a task? It’s irrational to add people to some tasks. As Fred Brooks observed in “The Mythical Man Month” if it takes a women nine months to gestate a baby, you can’t get a baby in a month by putting nine women on the job. That said, some tasks can be done more quickly (to an extent) by adding people – digging a ditch or building a house. It generally becomes less efficient the more people you add because of the increased communication and coordination overhead, and at some point, it makes no difference. If you need to write a 50-page white paper, find a subject matter expert who is a good writer. If you need one fast, get two or three and have them divide up the work. If five hundred writers try to help with the paper it may never get done – but it will be very expensive. That’s the law of diminishing returns. Which critical path tasks might be expedited by adding a subject matter expert? Which might benefit from adding an intern to run errands for the existing subject matter experts so they can focus on the task at hand?

Two) Where can you throw money at a task to safely make it go faster? A thought experiment that can inspire excellent problem solving is asking a team, “If money were no object, which tasks could we expedite?” This can be as simple as expedited shipping for materials or parts. On one project the best use of my time as assistant project manager was boarding a flight in the morning, flying to a vendor site 400 miles away to physically pick up a component we needed and flying home. It saved the project a critical couple of days waiting for delivery and cost a plane ticket and a day of my time.

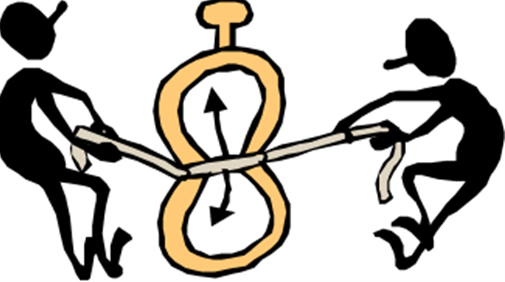

Three) Review task dependencies – Are you doing any tasks sequentially that could safely be done in parallel? The mechanics of scheduling can be mundane, tedious and error prone. Project managers are often so relieved when they get the task network established that they are loath to review or revise it. Some of the best planning advice I ever received was from a mentor named Pat Bell. She said schedules are like designs, evolving as we better understand the problem. Task sequence impacts schedule duration. Review dependencies and ask, “What is the nature of this dependency? Is it essential?” Beware task dependencies established to manage resources like people, or equipment, they hide resource constraints and assumptions.

I use the company van to do X in week one, then Rajul uses the van to do Y in week 2.

The implicit assumption is that there can only be one van, while renting a van might allow tasks to happen in parallel.

Four) Review the estimates – are they credible? What are the underlying assumptions? I’ve spent thirty years reminding people how to develop better estimates. I didn’t have to teach them, they knew. Define the task, identify metrics that will help you estimate the task, gather data where you can and make assumptions where you must and write them down, commit arithmetic with the metrics and assumptions, then review the results with someone knowledgeable and adjust based on their input. This helps tease out assumptions and build better, more reviewable estimates.

Lately, I’ve been convinced that an improvement on that process is to ask team members for 3-point estimates: best case, most likely case, worst case the person feels confident they can deliver. This gives people permission to eliminate “padding” and talk more seriously about risk. It also gives me a chance to say, “What would have to go well to get the ‘best case’ outcome?” Listen carefully, you are about to get some optimization ideas.

Five) Where might outsourcing speed things up? Long ago I was working for a consulting company developing a huge proposal for a client to submit to the feds. In addition to writing/accumulating the collateral for the 16 binders of the proposal, we had a non-trivial publication problem. The 16 binders represented over 6,000 pages of content. We needed to create 40 sets of the binders – perhaps a quarter of a million pages. The finishing touches were just being put on the “golden” binders – the reference set for duplication – when the head of admin came in and soberly said, “I just did the math and with all of our copy machines working at full speed we can’t make enough copies before the proposal is due.” A brash young consultant (me) ran to the local copy joint, threw down his credit card and asked them to reserve all their copy machines for the next 48 hours and bring in staff to support a graveyard shift – my enthusiasm and pridefulness somewhat diminished when the staff of the copy place informed me that they had REAL copy machines and what we needed was only a few hours work.

Can you paint the house yourself? Absolutely. Will a professional team with experience and professional tools be able to do it faster? Probably.

Six) Incentives for subcontractors/suppliers – This is a special case of throwing money at the problem that is sometimes overlooked because we assume that agreements are iron clad and immutable. Reach out to partners and ask what ideas they can offer for compressing their part of the schedule and what they would cost. It can’t hurt to ask, and suppliers can use some of the same tactics we are discussing here if you are willing to pay for them, such as expediting shipping rather than a more cost-effective slow boat.

Seven) Look for alternative approaches to the problem – One of my “go to” methods of trying to find low-hanging optimization fruit is to look for long duration tasks on the critical path and ask the team for alternative ways to accomplish that goal. If Thanksgiving dinner will require 12 hours of prep because of grandma’s secret recipe for brining turkeys, perhaps this year we see if a ham might be an acceptable and faster option.

Eight) Avoid multi-tasking – Multi-tasking is sometimes necessary, but almost always inefficient. If you want to optimize a task, try to get people to work on it full time without other distractions. I know a consultant who is considered one of the preeminent project managers in his field. People pay obscene amounts of money for his expertise. He is often asked, “If we could change just one thing about our operation to improve efficiency, what would that be?”

His advice is pretty consistent: “Have individuals work on one thing at a time.”

The response to this advice is surprisingly predictable. “We can’t do THAT. But if we could do just one other thing, what would that be?”

Nine) Can workdays be added to the schedule? – Most scheduling systems allow for a calendar to be created to define work time and non-work time. If your calendar says Saturday and Sunday are non-work times, changing them to work times gives you 40% more time to do the project. Working two shifts could double the available time again, if you can afford to staff them. This is NOT a suggestion to work your team seven days a week or 16 hours a day, that’s a recipe for disaster, burnout, and turnover at the worst possible time, but if you can get additional human resources to help off shift or over the weekend this can sometimes speed things up considerably.

Ten) “Crashing” tasks – This is last on the list for a reason, it must be used thoughtfully and sparingly to be effective. Crashing a task involves asking people to clear their calendar of all non-project work and non-work commitments to push hard for a few days to get a critical task done as quickly as possible. This is most applicable when resources can’t easily or effectively be added to a task. There are two ways to do this, one effective, the other dangerous.

None of these strategies are foolproof. All introduce potentially increased costs or risks that must be carefully weighed against the benefit of a compressed schedule. As I said in the disclaimer, your team will have more specific ideas better aligned with your project context, but these strategies can help start the conversation.

© 2018-2024, RTConfidence, Inc. | All Rights Reserved.